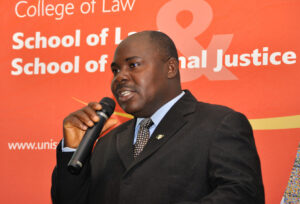

Being the 2nd Inaugural lecture delivered by Professor Don John O. Omale (Pioneer Professor of Criminology) at the Federal University Wukari, Taraba State, Nigeria held on 15th October, 2021.

Extracts:

The inaugural lecture began with the conceptualization of the term ‘restorative justice’ ‘as a problem-solving approach to crime which involves the parties themselves (victims and offenders) and the community generally, in an active relationship with statutory agencies (the judiciary and law enforcement agencies)’. Restorative justice according to the University don is also defined by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) as a participatory process which the victim and the offender, and, where appropriate, any other individuals or community members affected by a crime, participate together actively in the resolution of matters arising from the crime, generally with the help of a facilitator”.

According to the erudite professor the logic of restorative justice is that the “new is in the old contained, and the old is in the new explained” because the principles of modern restorative justice practices are contained in pre-colonial Africa principles, where many African citizens resolved their disputes using traditional and informal justice forums. But despite the popularity of this system among the Africans, these forums were regarded as obstacles to development during the colonial area (maybe due to a clash of paradigms between existing methods of doing justice and that of colonial power).The emergence of the restorative justice paradigm in the west has made the professor of criminology to argue for the transformation of the African restorative traditions in several international forums. This according to him is because restorative justice literature would be incomplete if the contribution of African restorative traditions to the emerging restorative justice paradigm is obscured or continued to be ignored, especially when some western criminologists and authors write about restorative justice history obscuring Afro-historical evidence. Others he said have even written that ‘when race are classified by colour, the only one of the primary races which has not made a creative contribution to any of the twenty-one civilisations is the black race’. Citing the work of Keulder (1998) professor Omale stated that ‘those who have criticised the African informal traditional justice system as being too traditional to promote development are often too simplistic in their arguments’, because the critics are bound up in the traditional-modern dichotomy in which ‘traditional’ to them is equated with ‘backward’ and ‘modern’ with ‘advanced’ initiatives. So to them, development could only occur within a ‘modern’ framework. The main problem with this equation, he argued, is that it is based on a very static and simplistic view of tradition because it ignores the fact that traditions are often ‘invented’ and, hence, very ‘modern’ in content. It is thought by these critics of African traditions that as Africa modernised the African informal and traditional justice would eventually die out. This of course the erudite professor argued did not occur because informal and traditional modes of dispute settlement in Africa have remained as widespread as ever, and even receiving international attention in the form of the ‘restorative justice paradigm’.

Hence professor Omale maintained that the informal and traditional dispute resolution approaches have remained relevant among most Africans for reasons that: the vast majority of Africans continue to live in rural villages where access to the formal criminal justice system is extremely limited, or that the type of ‘justice’ offered by the criminal justice courts may be inappropriate for the resolution of disputes between people living in the rural villages or urban settlements where the breaking of individual social relationships (ubuntu) can cause conflict within the community and affect economic co-operation on which the community depends, and /or that the criminal justice system in most African countries operates with an extremely limited infrastructure (with its attendant delays in administration of justice) hence, does not have the resources to deal with minor disputes in rural communities or villages. Other factors might include distrust of ‘criminal’ justice’ and a desire to avoid bringing trouble by involving remote (and sometimes corrupt) urban police in rural disputes.

Professor Omale who have been advocating for mainstreaming of restorative justice in the Nigerian criminal justice system since 2002, happily announced that at the time of the inaugural lecture, restorative justice has been nationally enacted and mainstreamed into the Nigerian criminal justice system as contained in the Nigerian Correctional Service Act of 2019 signed into law by President Mohammed Buhari. Section 43 (1) of the NCS Act (2019) provides that the Controller General shall provides the platform for Restorative Justice measures, including: (a) Victim-Offender Mediation, (b) Family group conferencing, (c) Community mediation, and (d) any other mediation activity involving victims, offenders and where applicable, community representatives. With the NCSA (2019), the time to ‘give restorative justice a fair crack of the whip’ in Nigeria is now.

He is an International Advisory Board member to the Restorative Justice Initiative Midland, UK, the Community of Restorative Researchers, UK and Restorative Justice International, USA respectively. He is also the “Africa Book Review Correspondent” to the International Journal of Restorative Justice at the Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium. He is a member of the World Society of Victimology and Fellow of the Institute of Criminology and Penology, Lagos, Nigeria. He is the author of a bestseller book titled ‘Restorative Justice and Victimology: Euro-Africa Perspectives’ published in The Hague, Netherlands by Wolf Legal Publishers; and the Founder of African Forum for Restorative Justice (www.africanforumrj.com)

His publications and citations are available at his Google Scholar, and ORCID page respectively. https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=nUgl97kAAAAJ ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6787-0674